At the grocery store the other day I chatted with the cashier as he rang up my purchases. He already had disinfected the moving belt at his checkout station, he assured me.

I commented through my mask, “Well, someday all of this won’t be necessary, when we get a vaccine.”

He snorted. “I’m not getting any vaccine. Do you want a bag?”

“Um—yes,” I said, trying to control my mental whiplash. “Why not? I mean, why won’t you get a vaccine?”

“I already got a flu shot,” he said, weighing my mangos.

I was dumbfounded but persisted. “Yes, but coronavirus is different than the flu.”

“Oh, I think it’s the same thing as the flu.”

Uh-oh, I thought, fumbling for my wallet. I am not going to convert this guy to rationality in the remaining thirty seconds we have together.

“What about other people?” I asked, appealing to his empathy.

“I hope they don’t give it to me,” he said.

Stunned, I uttered the usual, “Thank you” and “Have a good day” and pushed the cart to my car.

|

| Photo: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

Uppermost in my mind was the fact that no vaccine provides 100 percent protection from infection. (Most childhood vaccines are 85-95 percent effective, according to the World Health Organization.) If, when vaccines against coronavirus are available, a large portion of the population refuses to get them, where does that leave the rest of us? If I’ve gotten my vaccine and for me, it proves to be only 85% effective, and you haven’t had the vaccine and contract the virus, you can infect me. You can kill me.

Will we pass legislation requiring people to have the vaccine? Where do we draw the line between individual liberty and the collective good, and which will triumph? With a president who refuses to wear a mask, how will we persuade the masses that a vaccine is necessary and wise? (I cannot envision Mr. Trump with his sleeve rolled up, taking one for the team.)

Won’t the public end up footing the bill for the extraordinarily expensive health care of people who get the virus because they refuse to be vaccinated? And won’t we find ourselves in an endless loop of infection spikes?

|

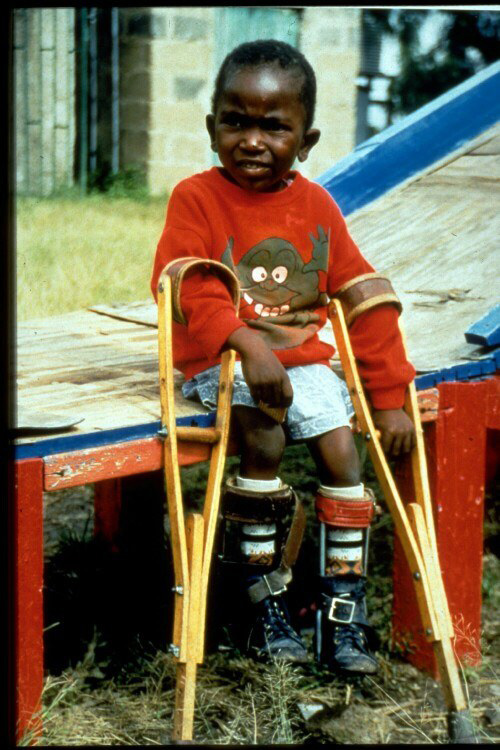

| Child with poliovirus Photo: World Health Organization |

I think part of the problem is that by and large, Americans do not remember the terror of infectious diseases that once killed and maimed. Smallpox killed three of ten people who contracted it, and it wasn’t eradicated in the United States until 1977. Among those who recovered from smallpox, many were disfigured for life. (Type into your browser the words “smallpox images” if you want to see its effects.) Polio outbreaks in the U.S. in the 1940s led to permanent paralysis in as many as 35,000 people a year, and to death from paralysis of the respiratory tract for many. Thankfully, polio was largely eradicated in this country 30 years ago through vaccines developed in the 1950s. Elderly people remember the horrors of these diseases. But only the oldest Baby Boomers have any conscious memories of polio, and likewise, the last smallpox outbreaks in the U.S. occurred in the 1940s. Smallpox and polio were highly contagious, like the coronavirus. By contrast, HIV/AIDS—the only real comparison in our lifetimes in the U.S.—is far more difficult to contract.

|

| One of my coronavirus heroes, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham |

The point is, the majority of living adult Americans have never seen what a highly contagious epidemic can do—until now. Yet today, many parts of the country—especially rural areas— remain largely unaffected. Our rate of infection in New Mexico is very low, in part because of our governor’s strong initial response, shutting down commerce early and taking other preventive actions, but also because our population is small and relatively spread out. (Only our brothers and sisters on the Navajo reservation are suffering high rates of infection and death, for many complicated reasons.)

Some people simply don’t believe in the coronavirus and won’t, until someone they know and love is infected and/or dies. Eventually that may happen for everyone in the country. Sooner or later, we may all know someone directly impacted by the virus.

By the time an effective vaccine is developed and available, will my cashier know someone who has had the virus? Will he change his mind about the vaccine? Or will he continue to live his ordinary life, contract the virus, and give it to his customers? Will his company require workers to get the vaccine?

The popular saying, “We’re all in this together” is so true, and not just for the coronavirus. Every time we take to the road in our cars, we hold each other’s lives in our hands. Our social contract dictates that we stop at red lights, go on green, yield when merging—and most of the time, most of us honor that contract. When we don’t, the consequences can be severe, for us and others. If we drive too fast, recklessly, drunk or otherwise impaired, we risk harming or even killing another person or people.

|

| How cool is this one? Photo: V-Helmets |

A closer analogy to the vaccine issue might be motorcycle helmet laws. Motorcyclists often argue that the only lives they risk when they ride without helmets are their own. That’s arguable. But the emotional price exacted when a helmetless motorcyclist is seriously injured or killed is enormous—to the motorcyclist, if she or he lives; to his or her family; and to the other driver(s) involved, who may or may not be culpable. Likewise, the motorcyclist who suffers a serious brain injury inevitably becomes a financial and medical burden on society, as we all end up paying for that care, directly or indirectly. One way or another, the collective suffers when the individual refuses to protect him- or herself.

The difference with coronavirus is that it is invisible. If we do not practice safe social distancing, if we refuse to take a vaccine when it is available, we may never know the direct impacts our choices make on others. That invisibility makes it easier to pretend that it doesn’t matter if we don’t wear our masks, stay safely separated from others, wash our hands, disinfect.

Our independent Western mindset encourages us to think of ourselves first and everyone else later. When I asked my vaccine-rejecting cashier, “What about other people?” his only concern was that someone else might infect him (he who doesn’t believe the coronavirus is any different than the flu. . .hmmmm). It did not even occur to him that he might infect others.

It’s hard to say whether his attitude was a result of ignorance or ego. Nor, in a way, does it matter.

I am wearing my mask, washing my hands, disinfecting, social distancing—and will take a vaccine when one is available—for me, yes, but also so I don’t have to wonder if I was the one who infected my beloved 93-year-old neighbor and thereby caused her death, or infected one person who was in contact with many others and then passed the gift of sickness and potential death on to a whole host of humans. Do it for yourself, do it for your neighbors, do it for the teenager who might one day grow up to be a virologist who can solve the next pandemic—if she can just make it through this one.

Whew. I need some chocolate.