We have all become so familiar with the symptoms of coronavirus that the slightest of aberrations in our health make us paranoid. A few nights ago, I literally woke myself from a deep sleep with one cough—yes, a dry cough—and had a moment of utter terror during which I was convinced I had contracted the virus.

Those of us who have not actually been infected with coronavirus have developed our own, sometimes persistent, symptoms. A friend and I compared our lists the other day: Eating more than usual. Gaining weight. Having difficulty sleeping. Watching vintage movies and television shows. Calling and emailing old friends and renewing lapsed relationships. Cleaning out the garage, or the closets, or both. Seriously stocking the pantry.

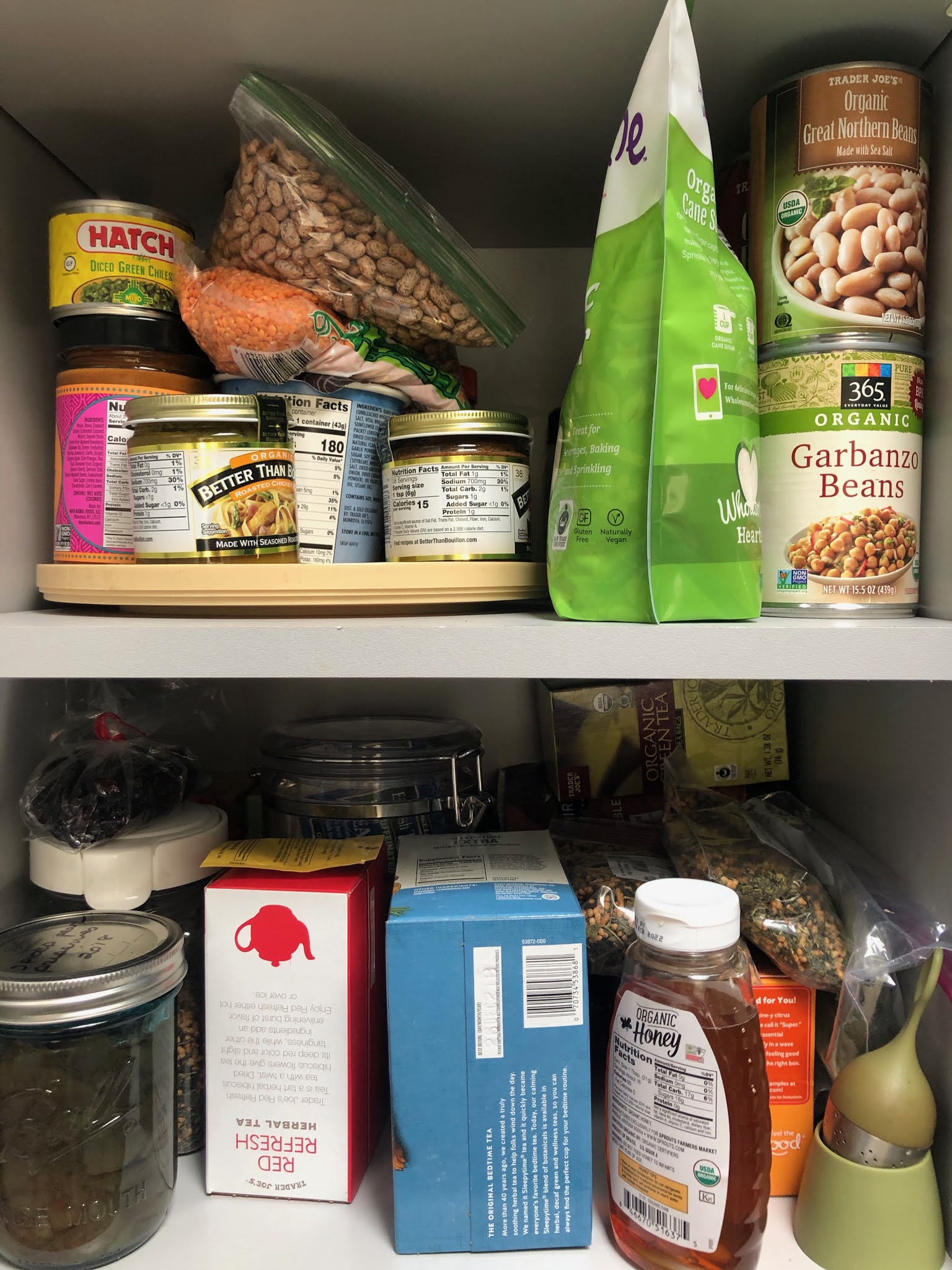

The latter is so utterly primal it’s laughable. Food, shelter, safety, society: these are among the most basic needs the human being tries to ensure will be met at all times.* Yet now that we have overcome (for the most part) our very real fears that breakdowns in the food supply will result in empty shelves and bellies, we are still buying more food that we need for a week or two. We have lots of beans and tuna fish and peanut butter, and the freezer is now full. (I realize that those who have lost their incomes may not have the luxury of over-shopping, but I also wonder if some of them aren’t doing something similar—going to every food pantry in the area, or going more often than necessary, driven by the same primal energies?) My friend commented, “It just makes me feel good to open the cabinets and see all of that food.” We are seeking comfort by ensuring our basic needs are met. Do I have enough? Am I okay today?

We are, I believe, compelled more often by these primal energies or imperatives than we would like to admit. And when the fear buttons in our brains are pushed, we are more likely to act out despite our best intellectualizing. Most of the time this kind of reaction is relatively harmless. Buying too much food will not disrupt the fabric of the universe (unless we have to start stacking it up in the bathroom and the kids’ rooms, in which case we need to call the therapist).

But it is fear that is at the root of racial hatred, in a very primal sense, I believe. We are afraid of those who look or act or dress or sound different than we do. Our primitive natures arise. Once upon a time, when we were all isolated in small tribal groups, to see another individual approaching us who looked different—taller, thinner, fatter, skinnier, more or less hirsute, darker or lighter skin and hair and eyes—surely that was threatening. Of course, now we have the knowledge and awareness to consciously overcome any vestige of primitive fear that may arise when we meet someone who looks or sounds or acts different from us. My mother grew up in rural Kansas and had never seen a black person except in the movies (think Al Jolson era) until she moved to the city at age 18, yet she had African American friends later in life. Yet I wonder how much those primal responses feed into the racism that plagues our country now.

|

| His Holiness the Dalai Lama |

I remember my first encounters with Tibetan people. My friend and photographer Kitty Leaken, with whom I worked at the Santa Fe New Mexican, was documenting the Tibetan resettlement project in Santa Fe, and had traveled to India several times to photograph the refugee Tibetan communities there, including the orphanages. We did some stories together about the Tibetans who had been resettled in Santa Fe. As I think back over that era (in the 1990s), I realize now that Kitty helped predispose me to a positive bias about Tibetans. I knew very little about Tibet, except for some knowledge of the Dalai Lama and his teachings. Kitty’s anecdotes about her relationships with Tibetans and my brief encounters with them as a journalist formed a picture of a strong and resilient people who had suffered a great deal and yet exuded warmth, compassion and humor. Every encounter I have had since with Tibetan-Americans in our community has been a positive one. How much of that is because of that initial “teaching” by Kitty and thus my beliefs about Tibetan-Americans? How much of how we react to different “others” is a result of how we have been prepared for those encounters?

Growing up in a military family and moving constantly, especially during my early childhood, means I missed a lot of the “normal” American experience. I feel that loss acutely when people talk wistfully about their hometowns, friends they’ve known since kindergarten, happy memories of spending holidays with extended family. But my experiences as a military brat also afforded me benefits some of those people didn’t get.

I lived among people of other races, religions and ethnicities all my childhood. Life on a military base was certainly not free of prejudices, but exposure alone makes a great difference in how one accepts or rejects people different from oneself. We shared our duplexes at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, and at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls, Montana, with Jewish families. (We were Protestant.) My Girl Scout leader at Malmstrom was African American, and her daughter was my friend and fellow Brownie. On Oahu, Hawaii, we lived off-base, among people of a mixture of ethnicities. My kindergarten and elementary school teachers there were native Hawaiian. In El Paso, Texas, I learned about Mexican American culture for the first time. These experiences made me less afraid of people different from myself, though I know that I surely harbor internal biases of which I am not even aware. But on first contact with people who are different, I am more often curious to get to know them than to be afraid of them.

Like other white Americans who are appalled at the recent events in our country, today I am struck by the harsh realities of life for African Americans and other people of color as never before. I have somehow felt more deeply what it must be like to go through life in America, “driving while black,” “birding while black,” “jogging while black.” To feel oneself in danger all the time—including danger from the very authorities charged with protecting our society—must have damaging consequences beyond my understanding. This constant added stress is surely one of the reasons (besides economic disparities) that black Americans suffer more health problems than white Americans, and now are suffering more drastic infection rates and consequences of coronavirus.

Our culture has reached a tipping point. Some days, when I read (and rarely, watch) the images of the protests and the continuing police brutality against protestors, I despair that our culture will ever change. I fear that our government is irreparable, that our society will never become equitable. At other times, when I see protestors trying to repair damage done to businesses during the protest, watch police officers march alongside protestors, hear demands for change that are rooted in rationality (job and health care equity, outlawing brutal police techniques, etc.) I am hopeful. My heart leaps when I see how many white people and people of other ethnicities are marching alongside African Americans. Perhaps this is the moment, the moment that was eclipsed by the complex and competing issues of the 1960s civil rights era. It seems to me that we were on the right track back then, but the Vietnam War, Watergate, and other explosive problems derailed us.

I pray that this time is different. The coronavirus draws more, not less, attention to the extraordinary inequities in our society for people of color (as did the Vietnam War, of course).** But perhaps when vaccines are available, the current health care crises will abate, and we can keep our eyes on the prize of creating a society in which all people are valued and enjoy equal rights. At this extraordinary point, may we tip into hope, into consciousness, into compassion. May we look to other cultures of people who have survived and thrived despite the greatest of odds stacked against them. The world is calling us to greater leadership than ever before, to model the painful but necessary behavior of change. This is a greater challenge than a war; we must harness our minds and hearts, without relying on weapons and polarization, to make the changes necessary to survive and thrive. May it be so.

*Read through Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs for an interesting refresher course: https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html#:~:text=Physiological%20needs%20%2D%20these%20are%20biological,human%20body%20cannot%20function%20optimally.

**Here is a good recap of discrimination and overcoming racial inequities on a personal level during the Vietnam War: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/18/opinion/racism-vietnam-war.html